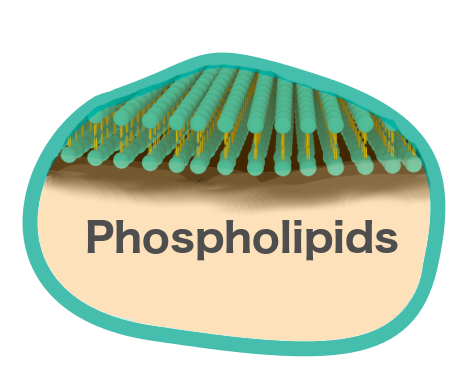

Liposomes are composed of lipids, which are amphiphilic molecules containing a hydrophilic head group and hydrophobic fatty acid tails. When placed in an aqueous solvent, the hydrophobic nature of the fatty acid tails lead to the self-assembly of lipids, likely resulting in the formation of liposomes. The aqueous interior of the liposome is surrounded by a lipid bilayer, similar to a cell membrane.[1] The analogous morphology and physiology of the liposome lipid bilayer to cellular membranes, provoked liposomes to be considered as excellent artificial cells, enhancing research in cellular membranes and cell-surface modifications.

The lipid bilayer surrounding the aqueous interior of liposomes keeps dissolved hydrophilic solutes from passing through the hydrophobic region. Similarly, hydrophobic molecules interacting with the hydrophobic tails inside the lipid bilayer cannot dissociate themselves due to the surrounding hydrophilic regions. Combined with their capability of being both biocompatible and biodegradable, these properties prompted the incorporation of liposomes in biomedical research, namely as molecule transport/delivery vehicles. Encapsulation of drugs and the subsequent delivery by liposomes can increase both the efficacy and therapeutic index of broadly toxic drugs. They can also reduce the toxicity of encapsulated molecules, avoid non-target tissue, and can couple with site-specific ligands for the achievement of active targeting.[2, 3, 4]

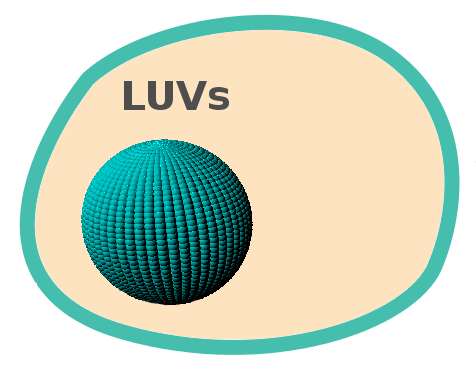

We plan to synthesize both Giant Unilamellar Vesicles (GUVs) as well as Large Unilamellar Vesicles (LUVs). The first step is to acquire simple phospholipids for use in the first synthesis of our liposomes. We plan to use 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), as its use in biomedical applications is well documented and can form more flexible liposomes than other lipids, a beneficial aspect in the encapsulation of highly hydrophobic molecules.[1]

Once we have established the synthesis of liposomes by a simple uniform lipid composition, we plan to move forward with more complex liposomal synthesis with the intention of later functionalizing them. Incorporating a small ratio of biotinylated 1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DPPE) into a solution containing DOPC would enable the synthesis of liposomes containing high binding affinity for streptavidin. This biotin-streptavidin binding system would allow for a high degree of characterization and wide technological applications.[2]

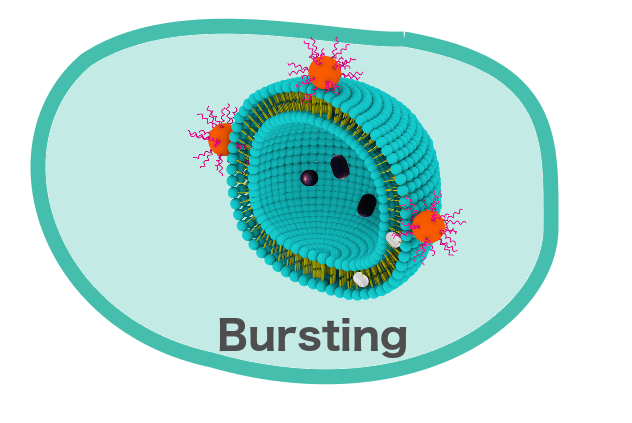

The diameter of the liposomes we plan to synthesis should be around 200nm, which would classify them under Large Unilamellar Vesicles. The plan is to design the liposomes with the intention of bursting them at a targeted location. Bursting has been well established with Giant Unilamellar Vesicles and does not require too many cell-bursting peptides.[3] To ensure the liposomes have a high probability of reaching their targeted destination, we plan to use 200nm liposomes, in which bursting has not yet been established and would theoretically be more difficult to burst. The small size of our liposomes would also allow for more precise attachment of the LUVs to the greater Nanorover system.

One problem that we will encounter in our use of LUVs is the diffraction limit of light microscopes, making it very challenging to view particles of approximately 200 nm.[4] For this reason, we plan to make use of super-resolution microscopy by imaging our samples with STORM.[5]

In an effort to determine the diversity of our cell-bursting peptides, we plan to synthesize GUVs. These GUVs would be visible using confocal microscopy and would provide us with very nice, detailed images. Upon addition of cell-bursting peptides, we should also be able to visualize GUV bursting under the confocal microscope.[6]

One of the cornerstones of our project is the bursting of the liposomes in a controlled way. We plan to conjugate the biotinylated cell-bursting peptides to a streptavidinylated quantum dot. This system would then burst both the LUVs as well as the GUVs.

After successful completion of the bursting of LUVs and GUVs, we also plan to modify the bursting experiment to include molecule encapsulation by the LUVs and their subsequent bursting. We would verify the release of the molecules from the liposomes by using ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy to quantify the concentration of the molecules.